Masada

One could also climb the zigzag "Snake Path" on the east, but this was dangerous and difficult before the modern authorities built it up. Well, it's still difficult.

The top is a plateau, 1900 feet from north to south and 650 from east to west.

One of the HasmoneansThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire starting in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's. first fortified it, but most of what we see is attributed to their successor, HerodHerod ruled the land under Roman auspices from 37 - 4 BC. After his death, he was called "Herod the Great." Christians chiefly remember him, however, as the killer of the innocent children (Mt. 2: 16).. This energetic ruler first tested the virtues of Masada as a young man struggling for power. His foes were then the Hasmoneans (more exactly, that part of the family that refused to collaborate with Rome) and their ally, the Parthians. Both groups were besieging him in Jerusalem. He made a break for it, together with his family and army. After narrowly escaping capture at the site of the future Herodium, he and his followers reached Masada. Here he installed his family, trusting that the natural strength of the place would protect them. He then went out on his own, seeking help. His search led him to Rome, where Octavian (later called AugustusOriginally Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar. He became one of the triumvirate, along with Marc Antony and Lepidus, that ruled Rome after Caesar's assassination in 44 BC. At the Battle of Actium in 31, he defeated Antony and became the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, remaining in power until his death in 14 AD. The Senate awarded him the name Augustus ("revered"), Sebastos in Greek. The stability during his reign introduced a Roman peace (pax romana) upon the Mediterranean world (a factor that later helped make possible the rapid spread of Christian faith).During his lifetime, Augustus allowed himself to be worshipped as a god in the provinces, though not in Rome itself. We find the ruins of his temples at Caesarea Maritima, Sebastia and Banias. After his death, his divinity permeated Rome.) and Marc Antony saw his potential and persuaded the Senate to name him King of Judaea. He returned (the whole journey had taken a year) and found that Masada had indeed protected his loved ones. With Antony's help, he went on to defeat his rivals, winning the throne in 37 BC.

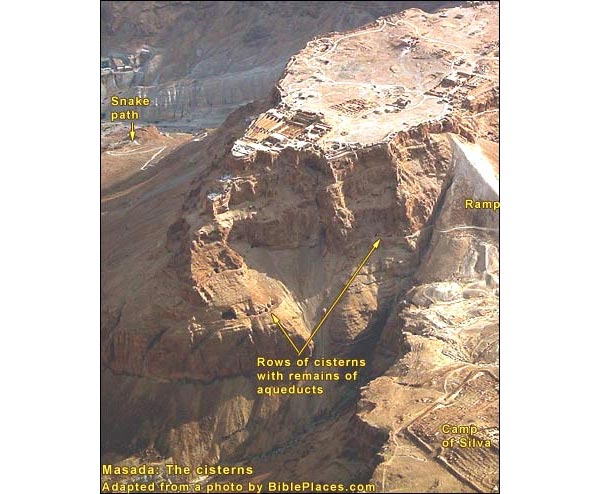

Once in power, Herod began restoring the ruined Hasmonean fortresses at the desert passes. He made of Masada a little paradise, replete with palaces, storehouses, pools, gardens and agriculture. Into this rocky hulk, which has no spring and gets hardly any rain, he dug and plastered cisterns with a total capacity of 40,000 cubic meters (about ten million gallons). Where did he get so much water? See the next article.

{mospagebreak title=Water Supply}

Masada's Water Supply

The cisterns in the sides of Masada can hold 10 million gallons. Before we answer the question of the source, we may ask why Herod needed so much water? This question touches on his motive for building here. Impressed with the mountain's natural defenses, according to JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist and a sentence (perhaps two) about Jesus, the Church preserved his works.:

Herod ...prepared this fortress on his own account, as a refuge against two kinds of danger; the one for fear of the multitude of the Jews, lest they should depose him, and restore their former kings to the government; the other danger was greater and more terrible, which arose from Cleopatra queen of Egypt, who did not conceal her intentions, but spoke often to Antony, and desired him to cut off Herod, and entreated him to bestow the kingdom of Judea upon her. And certainly it is a great wonder that Antony did never comply with her commands in this point, as he was so miserably enslaved to his passion for her; nor should any one have been surprised if she had been gratified in such her request. So the fear of these dangers made Herod rebuild Masada, and thereby leave it for the finishing stroke of the Romans in this Jewish war. (WarJosephus Flavius. The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston. VII 8.4.)

If his enemies ever got the upper hand, all Herod would have to do was reach the place that had earlier given his family refuge. Here he could live out the rest of his natural life, no matter what happened outside. He left the southern part of the mountain free, says Josephus, for agriculture. The water wasn't only for drinking, then, but for irrigation: to ensure a permanent food supply. The storehouses on the northern end also testify to this motive of independence. Here we have an island of self-sufficiency, a bunker of last resort.

Masada has no spring, and the annual rainfall comes to less than 100 mm., a fifth of what Jerusalem gets. Where then did he get 10 million gallons - that is, 40,000 cubic meters?

About a tenth of the supply came from the rain that fell here. On entering from the east, we can see that the central part of the plateau dips and narrows in our direction. Herod's architect gathered the run-off and led it to a cistern on the mountain's east side (visible upon leaving the cable car), by means of a drainage canal (also visible).

Yes, but where did the other 36,000 cubic meters come from?

To answer, we need to combine a little information with what we can see from the western side.

Information: It rains little here indeed, but it rains five times as much or more along the peak of the Judean mountain block from Jerusalem to Hebron. Half of this water flows downhill to the east -- into the desert, whose surface is chalk. At the touch of moisture, the molecules of the chalk swell up, becoming waterproof. The water flows on the surface, uniting and forming mighty flash floods near the Dead Sea a few hours later. (See photo below. For a biblical reference to the floods, see 2 Kings 3:4-27.)

What we can see: Looking west from Masada, we can see a gorge. Here Herod's engineers built a dam to catch the floods.

Near the top of the gorge they attached an aqueduct. They also dug and plastered cisterns in the western side of the mountain.They placed these over an abyss, high enough to be beyond an attacker's reach but low enough to catch the water, which flowed by gravity through the aqueduct. When one cistern filled, the overflow would go into its neighbor, and so on. In fact, they dammed two gorges (the other is around the corner of the cliff to the north) creating two such systems.

People would have to descend to the cisterns and bring the water up (to more cisterns on the plateau). For this purpose Herod had slaves. He provided them with a secret staircase and a wall, so that no one standing west of the abyss could see them.

An enemy could destroy the aqueduct! Indeed, but what good would it do them? The defenders of Masada would already have water enough in the mountain, much more than the besiegers. Until the Romans arrived in 73 AD, no major army had ever been able to stay for long in the desert.

How then did the besieging Romans, with ten or fifteen thousand soldiers, solve their water problem? After putting down the Jewish revolt in 70 AD, they had so many prisoners and pack animals, they could form a "bucket brigade" from springs in the Tse'elim river three miles to the north. We can still see the path of the "brigade."

{mospagebreak title=Herodian Structures}

The Herodian Structures on Masada

These include:

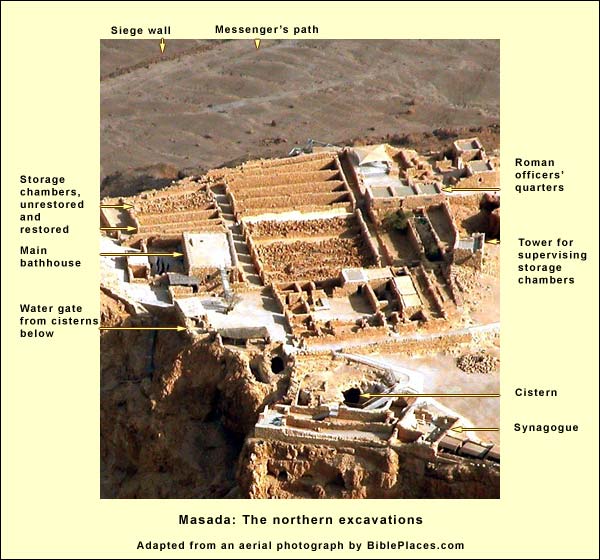

A casemate wall,A wall consisting of two parallel walls joined by short transverse walls, together forming casemates (chambers). three-quarters of a mile long, surrounding the entire plateau. Its outer wall was 5 feet thick (not enough to withstand a Roman battering ram) and its inner wall was 3. The Jewish rebels, too numerous to live in the palaces and villas, later adapted the casemates within the wall for living spaces.

The main administrative palace was on the western side. Among the surviving gems is a mosaic floor with a rosette pattern, interrupted by a crude construction of the Jewish rebels.

The mosaic belonged to the lukewarm room (tepidarium) of the palace bathhouse.Before the Empire, Roman baths were for bathing. After undressing, the bather would carry his towel, oil and scraper (strigil) into the warm room (tepidarium), to adjust for the torments ahead. Then he would enter the hot room (caldarium), which was heated by a hypocaust: oven-heated air flowed between two floors, which were half a meter or so apart. Here he would rub himself with oil, wait a while, and scrape it off. Then he would cross to the frigidarium, plunging into cold water. Under the emperors, baths came to include much more: work-out rooms, music chambers, libraries, gardens, art galleries, shops and a very public WC. The bath became a major center, perhaps the major center, of a city's life. The hot room (calidarium) contains Herod's bathtub, which is rather narrow. Apparently he wasn't so great. Yet a bathtub discovered at Kypros, another of his fortresses, is much bigger.

South of this main palace are two family villas and what may have been a public ritual bath. Around this bath are niches, used as "lockers" perhaps, enough for about twenty people.

Built into the casemate wall, on the northwest, is a chamber larger than the others in the wall. Unlike the buildings on Masada, which have a north-south axis, this one points toward Jerusalem. The rebels used it as a synagogue, and it may have functioned as such already in Herod's day. There was a synagogue, after all, in the royal quarter of Jericho. (More about the Masada synagogue...)

West of the synagogue, on a higher level, is the main bathhouse, restored to good condition. We can stand on its roof to survey the northern half of the mountain, especially the large rectangular chambers for storage of foods and beverages.

Inside the bathhouse are four basic chambers: the dressing room (apoditarium), some of whose frescoes and floor tiles are well preserved; the cold room (frigidarium); the tepidarium; and the hot room or calidarium. In this last, the small pillars supported a second floor. Between the floors flowed oven-heated air, which proceeded up ceramic pipes. The vaulted ceiling prevented the condensed moisture from dripping on the sweating aristocrats.

Just north of the bathhouse we see a plastered wall; it stretches across this narrow part of the mountain. Behind it is the upper ledge of Herod's three-tiered northern palace. He built it as an abode where he could get away from the rest of the family -- hence the wall. In view of the fact that he executed Mariamne, his beloved wife, and later his three eldest sons, we are justified in supposing there were problems in that family. (More about the northern palace... )

{mospagebreak title=Northern Palace }

The Northern Palace

Just north of the bathhouse we see a plastered wall; it stretches across this narrow part of the mountain. Behind it is the upper ledge of Herod's three-tiered northern palace. He built it as a refuge from the rest of the family -- hence the wall. If Masada itself was designed as a refuge, then here was a refuge within the refuge!

Herod chose the northern end for his private "hideaway," because it turns its back to the sun and, jutting out, gets the dominant southwest breeze.

The palace has three tiers. The upper one was the residence. It affords a panorama to the north and east. Note the green strip of Ein Gedi, six miles distant (photo below). We can also see the path of the water carriers who supplied the Roman army; it leads toward springs three miles away.

Directly below are the two lower tiers, which served as pleasure gardens. Herod's builders enlarged the mountain with retaining walls to provide sufficient space.

We can reach these lower tiers by descending a staircase (southwest of the "privacy wall") of 160 steps. Pausing in the middle tier, we find a section of Herod's own winding staircase. This tier probably had pillars supporting a roof. The circular channel may have contained water.

The lowest tier is the best-kept part of Masada. Many frescoes were preserved under rubble and have since been restored (enlarge photo on right). We note the scrupulous avoidance of images. The lines are soft, because the artist would paint in fresco, that is, he would paint the fresh plaster while still wet; the colors wouldn't fade, therefore, when the wall was washed.

Each pillar was made of sections, which were plastered over to resemble a single stone. So it was with all the pillars on Masada. The plaster apparently fooled JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist and a sentence (maybe two) about Jesus, the Church preserved his works. (or more likely, his Roman informant): "These buildings were supported by pillars of single stones on every side," he wrote. (WarWar= Josephus Flavius. The Jewish War. Translated by William Whiston. (Abbreviated in text as War.) VII 8.3) Josephus made another error too: he mixed the northern palace up with the western one.

This lowest tier had its own bathhouse on the east. Here and in the grounds nearby, beneath ash, the archaeologists found human remains, including a woman's braid. There were sandals, arrows and scales of armor. Archaeologist Yigal YadinYigal Yadin, Masada: Herod's Fortress and the Zealots' Last Stand, New York: Random House, 1966, p.54 attributed these to Jewish rebels (as he did 25 skeletons found in a cave on the southern end). An Israeli researcher has disputed these claims (ZiasZias, Joseph. "Whose Bones?" Biblical Archaeology Review, November/December 1998. ).

{mospagebreak title=First Jewish Revolt}

Build-up to the First Jewish Revolt Against Rome

1. The Jewish king of Judaea, Agrippas I, dies in Caesarea (43 AD).

2. The Romans return to the system of sending procurators.

3. Rebel bands appear ("robbers" [Gr. lestes] JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist and a sentence (maybe two) about Jesus, the Church preserved his works. calls them.) One of these bands, first appearing in the 50's, was that of the Sicarii A Jewish nationalist group. From the Latin, sicarius, meaning "dagger-man," which in turn goes back to the word sica, "dagger." "These men," wrote Josephus, "committed numerous murders in broad daylight and in the middle of the City [Jerusalem - SL]. Their favorite trick was to mingle with the festival crowds, concealing under their garments small daggers with which they stabbed their opponents." The Sicarii first appear in the 50's AD, but Menahem, their leader, was the son or grandson of Judas the Galilean, a rebel from the time of Jesus' childhood. They occupied Masada, where their synagogue and ritual baths testify to their piety. or "dagger men." It was also a time of "false prophets," "seducers" and "deceivers." (Josephus' WarJosephus Flavius. The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston II 5.2-3). These "robbers" and "deceivers" were apocalyptic eschatologists, as is evident from the sequel to the Masada story in Josephus, although he downplays their motives. (Why?)

4. Under Nero, the procurators become increasingly corrupt. The Jewish and Gentile residents of Caesarea get into a dispute over land beside the synagogue. The Jews bribe Florus, the procurator, to rule in their favor; he takes the money and spurns them. Then he sends forces to the Temple treasury, seizing silver. When the Jews of Jerusalem protest, Florus goes up to Jerusalem with an army. In response to the mockery of a few youngsters, he erects a judgment-seat outside the palace (in the Armenian quarter of today, south of the Jaffa Gate) and orders his soldiers to sack the marketplace. They not only sack, they massacre. Florus has some Jews crucified. When the mass of the Jerusalemites continue to defy him (cutting the colonnades that link the Temple to the Antonia Fortress), Florus feels threatened and returns to Caesarea, leaving a Roman garrison in the Citadel near the Jaffa Gate.

5. "Meanwhile, some of those most anxious for war made a united attack on a fort called Masada, captured it by stealth, and exterminated the Roman garrison, putting one of their own in its place" (Jewish WarJosephus Flavius, The Jewish War, translated by G.A. Williamson, Penguin, 1981., II 408 [17.2]. My italics.). Later (IV, 391-417) we find Masada in the hands of the Sicarii, so it must have been they, apparently, who captured it. In order to capture the mountain "by stealth," the rebels would have had to take a route which the Romans would not have thought possible - that is, a route where the Romans would not have posted guards. One possibility is indicated in the photo below. Presumably the Sicarii would have gagged themselves while climbing, so that anyone who fell would not spoil the surprise.

6. The leader of the Sicarii, Menahem, finds weapons at Masada and takes them to Jerusalem, where he fans the revolt. In Jerusalem the Jews are split between rebels and peacemakers. Within the Temple command, some refuse to make sacrifices in honor of Rome and Caesar. Amid rivalry between rebel groups, Menahem is killed. His cousin, Eleazar ben Ya'ir, escapes from Jerusalem with a small band to Masada. They remain here for the rest of the revolt.

7. The rebels who killed Menahem surround the Roman garrison in the Citadel, which surrenders. As these are leaving the city, having put down their arms, the rebels massacre them. They do this on a Sabbath, and now most of the Jews in Jerusalem expect terrible Roman revenge.

8. In Caesarea, the Gentiles massacre the Jews. Throughout the country, Jews turn on Gentiles in reprisal. Thousands die on both sides.

9. The Roman legate in Syria, Cestius Gallus, realizes at last that he has a problem. He comes with a legion and lays siege to Jerusalem. But then, for reasons that Josephus cannot fathom (and which we, therefore, don't know) he "recalled his soldiers from the place, and by despairing of any expectation of taking it, without having received any disgrace, he retired from the city, without any reason in the world." (WarJosephus Flavius, The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston. II 8.7) This encourages the rebels, and they pursue his troops down the ridge of Beth Horon. In the narrowest place, they block the Romans and force them down the steep slope into the ravine, decimating much of the legion. Cestius manages to escape with a remnant to Caesarea.

10. "But as to those who had pursued after Cestius, when they were returned back to Jerusalem, they overbore some of those that favored the Romans by violence, and some they persuaded to join with them, and got together in great numbers in the temple, and appointed a great many generals for the war" (Ibid. II 9.3). These generals include Eleazar, chief of the Zealots (not to be confused with Eleazar son of Ya'ir, leader of the Sicarii on Masada), one "John the Essene," and Josephus himself.

This is the moment when the great mass of the people joins the revolt. Perhaps many do so under compulsion. They have, besides, a precedent: the successful Maccabean revolt against the Greek Empire. But it is likely that some see the three successive victories, culminating in the defeat of a whole Roman legion, as a sign that God has re-entered history on their side. How else can we explain the fact that even the separatist Essenes joined in?

The Roman response was at first in the nature of a punitive action. But political circumstances in Rome, of which the Jews probably had no inkling (as little inkling as the Romans had of the Jewish covenant faith) would greatly increase the importance of the campaign against Jerusalem. {mospagebreak title=Masada and revolt} Masada and the first Jewish revolt against Rome The Jewish revolt of 66 AD caught the Romans by surprise. The Jews had enjoyed "favored-nation" status ever since the decrees of Julius Caesar. The Romans probably thought they were conducting an enlightened occupation. There had been small-scale uprisings since Herod's death in 4 BC, but nothing had prepared them for revolt en masse. The extraordinary factor in bringing on the war wasn't Roman behavior, but the Jewish covenant faith, of which the Romans understood little. By the terms of God's covenant with Israel ( Deut. 11: 13-17), many Jews believed that because they no longer worshiped idols, they ought to be sovereign in their land. The Roman occupation was therefore a challenge to the heart of Jewish belief. Various groups, such as the Essenes or the movements behind John the Baptist and Jesus, understood the Roman occupation to signify the travails of the final days. These "birthpangs,"Mark 13:8, "For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. There will be earthquakes in various places. There will be famines and troubles. These things are the beginning of birth pangs." they thought, would usher in Redemption. Some of them believed that Redemption would result from a war against Evil. The Essenes, for instance, grouped the Romans with the Sons of Darkness. They joined the revolt, which they must have seen as the final war. (More on the "birthpangs of Redemption"...) The historian of the Jewish revolt was JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist and a sentence (maybe two) about Jesus, the Church preserved his works. (also our sole ancient source for the events on Masada). Yet here we run into a problem: Josephus avoids the topic of apocalyptic eschatology. With one exception, his history gives no idea of the part such thinking played in causing the war. Here is the exception:

But now, what did the most elevate them in undertaking this war, was an ambiguous oracle that was also found in their sacred writings, how, "about that time, one from their country should become governor of the habitable earth." The Jews took this prediction to belong to themselves in particular, and many of the wise men were thereby deceived in their determination. Now this oracle certainly denoted the government of Vespasian, who was appointed emperor in Judea. (Wars... Josephus Flavius. The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston VI 5.4) "What did most elevate them in undertaking this war"! Only now, near the end of the book, does our historian mention the principal motive of the war, with a bow to Vespasian! In Book II of his history, Josephus describes in some detail the events leading up to the revolt. Yet there he doesn't mention "what did most elevate them in undertaking this war," except for a cursory dismissal of "false prophets" and "deceivers." For reasons of his own life and livelihood, he did not want to write about the topic. (Why not?) We shall remember this deliberate omission when considering his account of Masada. In 66 AD, Josephus tells us, while Jerusalem was in turmoil, "some of those most anxious for war made a united attack on a fort called Masada, captured it by stealth, and exterminated the Roman garrison, putting one of their own in its place" (Jewish War,Josephus Flavius, The Jewish War, translated by G.A. Williamson, Penguin, 1981. II 408 [17.2]). Later (IV, 391-417) we find Masada in the hands of the Sicarii; it was they, apparently, who captured it. In order to capture the mountain "by stealth," the rebels would have had to take a route which the Romans would not have thought possible - that is, a route where the Romans would not have posted guards. One possibility is indicated in the photo below. During such a climb, however, anyone who fell would instinctively cry out, and this would have ruined the surprise. Presumably the Sicarii would have gagged themselves for the climb.

The Sicarii were pious Jews, as evinced by their synagogue on Masada, as well as two ritual baths built in accordance with Jewish law (halakha). Their relation to a group called the Zealots is unclear. (See SternStern, Menahem. "Zealots," Encyclopedia Judaica Year Book, 1973. Jerusalem, 1973., pp. 135-152.) The cardinal point of their movement, stresses Josephus repeatedly, was "to serve neither the Romans nor anyone else, but only God." They were an apocalyptic group: that is, like the Essenes and others, they believed Redemption was near. How do we know this? First, there is a general point: the Sicarii instigated the revolt, whose chief motive, Josephus indicates, was Messianic. But there is also a particular piece of evidence, which creeps in despite his avoidance of the topic: In the book's last few pages, Josephus mentions one Jonathan, a member of the Sicarii, who escaped to Cyrene (in Libya of today). Here he "prevailed with no small number of the poorer sort to give ear to him; he also led them into the desert, upon promising them that he would show them signs and apparitions." (WarJosephus Flavius. The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston VII 11.1) The Sicarii stayed on the mountain throughout the revolt, sometimes plundering the area for food. On one occasion they overran Ein Gedi, a Jewish town six miles north of Masada, dispersing its inhabitants. "As for such as could not run away, being women and children, they slew of them above seven hundred. Afterward, when they had carried every thing out of their houses, and had seized upon all the fruits that were in a flourishing condition, they brought them into Masada. " (WarJosephus Flavius,The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston., IV, 7.2) Thus the famous rebels on Masada had no hesitation, if we believe Josephus, about massacring their fellow Jews: men, women and children.

The Romans took Jerusalem in 70 AD, quelling the revolt. The Jews had suffered enormous losses. Some rebels managed to flee to the fortresses at the desert passes of Herodium, Machaerus and Masada. In 72 AD the first two of these surrendered, leaving 967 Jews still free on Masada. That freedom was an embarrassment to Titus and Vespasian, who had already celebrated their triumph over the Jews in Rome. This victory was their sole claim to fame, hence the sole basis for their authority. Vespasian, therefore, ordered the Roman governor of Judaea, Flavius Silva, to eradicate this last rebel stronghold. Silva showed up in 72 or 73 AD with "all the forces available." Thus the Jews, most of whom lived in the casemate wall, one day looked over the side and found themselves surrounded by the Tenth Legion and its auxiliaries: six to ten thousand Roman soldiers, with at least as many captured Jewish slaves. The Romans were busy building a wall down below, sealing off the mountain. They also constructed siege camps. Eight are visible today, including one atop the nearest mountain to the south; from here they could observe the top of Masada. Because it rains so little, there is hardly any erosion, and inside the camps one can still make out the roads, the bases for tents, even a triclinium (the dining room of the officers). Only earthquakes have shaken the walls down: once they were nine feet high. Near points in the wall where the rebels could have attempted a sortie, one can still see turrets for mounting catapults.

Silva had a topographical problem. He would have wanted to finish the work in a winter (and did, in fact, by the 15th of Xanthicos, which would have been in May; there is no basis for the popular notion that the siege lasted three years). He knew that the Jews had plenty of water in the cisterns. They could cultivate the southern part of the plateau, as Herod had. He could not simply sit and wait: he would have to attack. To assault the mountain from the east, up the Snake Path, was clearly impossible (a 1200-foot climb).

On the west, however, the natural saddle offered a chance, if he could build an assault ramp on it. Silva pitched his camp, therefore, on the west. But here was the rub. The Roman army never initiated anything significant on a given day without an oracle from the gods. How did they get the oracle? The priest, at sunrise, spread grain for the "prophetic chickens" and let them out of their coops. If they ate with appetite, this was a good omen. If not, the Romans had better stay put. (See Graves, Robert Graves, I Claudius, Penguin: 1977 p. 19, for the melancholy story of an admiral who did not revere his chickens.) Yet if the priest stood waiting for the sunrise in Silva's camp on the western side of Masada, he wouldn't see it till late morning -- and the winter days were short. He could see the sun much earlier from the eastern side, without that hulk directly in front of him. The topography, then, forced general and priest to separate. The priest on the east would get his oracle and then send a messenger to Silva in his camp on the west. We can still see the path of the messenger just beside the wall.

From his station on the west, Silva commanded his men to erect a ramp broad and strong enough to support a tower. By using the natural saddle that joined Masada to the cliff on the west, they would need to add 90 feet of height. They built a frame of tamarisk trunks (some of which still poke from the sides) and onto this they heaped white soil. From the moment construction started, the Jews knew exactly the point they had to defend. They could shoot at the builders or roll stones down on them. Such a stone could do its work without a direct hit, because each was large enough to cause a mini-avalanche. (This may be the explanation for some of the great rounded stones found on Masada near the assault ramp.) The question, then, is how the Romans managed to build this ramp.

A popular explanation is that they used Jewish slaves. But that would hardly have given the rebels pause. They'd had no compunctions, as noted above,See above. The source is Josephus Flavius,The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston. War IV, 7.2 about massacring Jewish women and children for lesser reasons. Perhaps the Romans worked by night under protective roofs. And/or: perhaps they employed the principle Pompey had used when he built ramps against Jerusalem: he erected them on Sabbaths, and the Jews did not resist (WarJosephus Flavius, The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston I. 7.3). Since the Maccabean revolt, they would fight on Sabbath only in direct self-defense. (An exception.)

One way or another, the Romans managed to get the ramp close enough to bring in their catapults, which hurled stones to cover their work. They finished it and hoisted up onto it a huge iron-plated tower. Ninety feet high, it contained a battering ram and a staircase. They then began to batter the casemate wall. Seeing it beginning to give, the Jews built a stronger wall behind it, composed of a pliant wooden frame and earth. Having broken through the first, the Romans began pounding this new wall, but the more they battered, the firmer it got. According to archaeologist Ehud Netzer,“The Last Days and Hours at Masada.” Biblical Archaeology Review, Nov/Dec 1991, 20-32. http://members.bib-arch.org/publication.asp?PubID=BSBA&Volume=17&Issue=6&ArticleID=13 who excavated here both with and after Yadin, the rebels would not have waited until the last minute to build the wall of wood and earth. They would have realized that Herod's casemate wall, 5 feet thick on the outside, could not withstand a Roman ram. Netzer finds evidence for the wooden-earthen wall in the fact that the archaeologists discovered charred wood and ash in only certain buildings on Masada. The fire lit by the rebels on their last night did not spread from roof to contiguous roof as one would expect. The reason, he suggests, is that the wood of the roofs in the unburnt rooms was simply not there when the fire was lit! In these cases, the roofing wood (consisting perhaps of palm trunks) had already been taken for use in the new, wooden-earthen wall. At the point nearest the natural saddle, where the Romans were building their ramp, the rebels must have pulled down the inner part of the casemate wall and built their wooden-earthen wall against the outer part. They would have piled and bound the 13-16-foot palm trunks lengthwise, their ends abutting the outer wall. On the east side of this mass of timber they'd have piled earth, held in place and reinforced by more wooden beams, and then, to back it, another section of wooden wall, composed of shorter beams. Estimating on the basis of the unburnt rooms (how much wood each would have required for roofing), Netzer figures they must have used 4000 long beams plus hundreds of shorter ones. The new wall would have been 70 to 80 feet long, about 60 feet wide, and 24 to 27 feet high (higher than the casemate, forcing the Romans to build their ramp higher). After ramming through the original casemate wall, the Romans rammed the new wall, only succeeding in making it firmer. But Silva saw that wood had been used. He ordered his soldiers to throw torches. The rebels must have prepared this, but their measures did not work. The wall caught fire. Yet a gust from the north blew the flames back against the Romans and their machines. "For a moment they stood aghast, but after this, on a sudden the wind changed into the south, as if it were done by Divine Providence, and blew strongly the contrary way, and carried the flame, and drove it against the wall, which was now on fire through its entire thickness." (WarJosephus Flavius, The Jewish War. Translated by William Whiston. VII 8.5). It was getting dark. The Romans withdrew, writes Josephus, planning to attack the next day. They posted guards to prevent escape. The Jews, for their part, sat in council to consider what to do in the situation. At this juncture Eleazar ben Ya'ir made a lengthy and eloquent speech in two parts. The second often corresponds to sections of Plato's Phaedo. The gist is this (in paraphrase): "Comrades, we face two alternatives. If we remain alive tomorrow, we shall be in the hands of the Romans. They will torture our children to death before our eyes. They will rape our wives and kill them. Then they will keep us as slaves -- us, who long ago took an oath to serve God alone! And what is the other alternative? Not to be alive tomorrow! Rather, as lovingly and painlessly as we can, let us dispatch our families and ourselves. On seeing this, the sadistic Romans will be disappointed, as well as awed by our courage in having preferred death to slavery!" (Excerpts from the speech.) At length Eleazar persuaded them. They went and killed their families. After burning their possessions, they met again and cast lots. Ten were chosen. The others returned to their dead, and the ten made the round, killing the fathers. They, in turn, cast lots, and one was chosen. After killing the nine, he set the palace on fire and fell on his sword beside his family. The next morning the Romans came up, charging out of their tower through the breach. Finding no resistance, they let out a shout. Two women and five children emerged; they had hidden in a cistern. One woman "gave a lucid report of Eleazar's speech and of the action that had followed." She then led the Romans to the burning palace, where they put out the fire and found the dead bodies in rows. Thus far Josephus. One archaeological find may relate to the story. In a long chamber next to the large bathhouse, the diggers discovered a group of eleven pottery shards, each with a name written on it, including the name Ben Ya'ir. Could these have been the lots? Yet there are problems with Josephus' account. First, the suicide. Brave fighters do not kill themselves. Even in a hopeless situation, they fight to the last. At the very end of his speech, Ben Ya'ir says that suicide "is what the Law ordains." Religious Jews, such as those on Masada, do not permit suicide except when they are commanded to worship idols, engage in illicit sexual acts, or commit murder. There are other problems too. After they have finally breached the wall, why did the Romans pull back and wait for morning? The rebels could have used this pause to erect a new wall. Besides, the morning sun would have shone in the Romans' eyes. And what if the sacred chickens weren't hungry? Did the Romans perhaps pull back to allow Eleazar time to make a profound and glorious speech, thus giving Josephus a nice rhetorical ending? Moreover, the Jews had known for weeks or months that the Romans would attack at this one point. They also knew that a casemate wall is not as strong as a solid one. Why didn't they strengthen it weeks before? And wouldn't they have made contingency plans well in advance? There is also a theological problem. Josephus did not want to mention apocalyptic eschatology (Why not?), but it must have been central to the faith of the Sicarii, as indicated above. Upon hearing the speech of Eleazar proposing suicide, an eschatologist would have objected: "There is a third alternative! Didn't we begin this war in the faith that God would intervene? Now, when everything looks hopeless, is precisely the time of testing. God has waited till all odds seemed against us, in order that the miracle may be greater! Therefore, we must fight tomorrow morning in the faith that God will give us victory! Consider the example of Abraham. When God ordered him to sacrifice his beloved son, they traveled three days to the appointed place. God didn't intervene on the second day and say, 'Abraham, I see you're serious. You can go home now.' No, he waited till the father had lifted the knife above the son! So now, our faith is being tested. The knife is raised. Let us stand the test!" If someone had made such an objection, what could Eleazar have answered? On the other hand, if the suicide were a fabrication, wouldn't some eyewitness have exposed the historian as a liar? Curiously, the Masada story does not quite end the book. "The next incident," we are told, "occurred in Egypt...Some members of the party of the Sicarii had managed to escape to Alexandria, where...they started a subversive movement." They numbered more than six hundred. The Jewish community of Alexandria betrayed them to the Romans, who subjected them and their children to the tortures foreseen in the speech of Eleazar. This happened sometime between March and August of 73 AD. Where could these people have escaped from? The revolt had been quelled in 70. Herodium and Machaerus had surrendered in 72, but Josephus does not mention Sicarii in either of them. Could these escapees have come from Masada? (See, for example, what had happened earlier at Gamla.) In short, we do not know whether the mass murder-suicide really occurred, nor have the stones been kind enough to say. We do know this: The Masada story remained insignificant to the Jewish people (the Talmud does not mention it) until the Zionist movement took root in Palestine. In 1927 Yitzhak Lamdan wrote an epic poem in which Masada functioned as a symbol for the whole land of Israel. The poet presented it as the last stronghold of the Jewish people. He included the line, "Masada shall not fall again!" Just as this mountain was surrounded by enemies, so the Jews of Palestine saw themselves surrounded. Josephus' account, true or not, inspired sacrifices on the Jewish side in the War of 1948. "Here is Masada!" cried one. "But this time we are fighting to save Jerusalem!" The story, therefore, was a factor in the creation of the present reality. We are such stuff as dreams are made of. The dream has dissolved. After military successes in 1956 and 1967, the War of 1973 proved a catastrophe for Israel. Many laid the blame on overconfidence and complacency. They began to look critically at Zionist legends, including the ever-dubious story of the suicides on Masada. In a letter to the New York Times on May 5, 1974, Israeli author A. B. Yehoshua wrote: "Our stiff-neckedness and arrogance derive from a lack of confidence in the world. It's a terrible irony that our fears create our own traps. Masada is far more today than just a national symbol. It is like a self-fulfilling metaphor that colors our everyday life. Every Israeli carries that hill around inside him; and the obsession only serves to bring the reality closer. The only way to shed our fatalism is to break our preoccupation with the past and learn to improvise. We must create a new Jew." Until a few years ago, the Armored Corps and the Paratroopers, having finished their training, would make a torchlight procession to the top of Masada and here take the oath of service, culminating in the cry from Lamdan's poem, "Masada shall not fall again!" Today they prefer more recent battlefields. Occasionally, the Engineering Corps holds a ceremony here. {mospagebreak title=Synagogue} The Synagogue Built into the casemate wallA wall consisting of two parallel walls, joined by buttresses that thus formed chambers. In time of need, these chambers could be filled to strengthen the wall. Otherwise they could be used for storage, or people could live in them (the Jewish rebels on Masada, for example)., on the northwest, is a chamber larger than the others in it. Unlike the buildings on Masada, which all have a north-south axis, this one points toward Jerusalem. The rebels used it as a synagogue, but it probably functioned as such already in Herod's day.

How do we know it was a synagogue? For the period of the rebels, 66 AD-73 AD, the evidence is firm. Apart from the orientation, there are the bleacher-like rows on the sides (now restored). Yigal YadinYigal Yadin, Masada: Herod's Fortress and the Zealots' Last Stand, New York: Random House, 1966, p.181 ff. , the chief archaeologist, was able to determine that the rebels had built them. Such a seating pattern, enabling discussion, is universal for ancient synagogues -- and for their orthodox descendants today. The crowning evidence, however, consisted of pits containing biblical scrolls (chapters from Ezekiel and the last two chapters of Deuteronomy). When pages including the name of God become worn or damaged, pious Jews do not simply throw them away. They store them in a synagogue, in a hole or chamber called a geniza, before burying the lot in a special ceremony. Here we have an ancient example of the practice. This synagogue on Masada was the likely venue for the rebel councils of deliberation. It was built (or rebuilt) for perhaps a 150 people, although after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, the population of Masada swelled, wrote Josephus, to 967 men, women and children. There were many synagogues before the Temple burned. Jesus taught in several. Paul preached in synagogues throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The Talmud says there were 400 in Jerusalem alone. Yet so far the remains of only three from this time have been discovered in the land: here on Masada, at Gamla on the Golan Heights, and in Jericho. (The one at Herodium apparently postdates the Temple.) One reason for the scarcity: people built new synagogues on the sites of older ones, which they tore down and leveled if necessary. Jews never resettled Masada and Gamla, so the traces of the earlier buildings remain. As for the one at Jericho, it was a royal affair: after an earthquake destroyed it (and after he had destroyed his young brother-in-law, the High Priest), Herod cavalierly built a palace on the spot. Synagogues were vital to the survival of Judaism. After the loss of the Temple, with the Jews in dispersion, they had only words and practices to keep them together. Lacking guidance from the Temple in interpreting the words or defining "orthopraxis," they might easily have splintered into numerous sects. Through the synagogues, however, the Sanhedrin was able to disseminate teachings and enforce them. Its Rabbis transferred certain major Temple rituals to them: prayer replaced sacrifice, and services were scheduled at the times of the former communal offerings. Vital parts of synagogue worship, such as the public Torah reading, required a quorum (minyan) of ten Jewish men. Jews had to live near one another, therefore, in order to fulfill their religious duties. Peoples conquered by Rome were not permitted freedom of assembly. Perhaps because of the support the Jews gave him in his war against Pompey, Julius Caesar granted this freedom to the Jews, along with other exceptional privileges (Caesar's decrees). After the first revolt, the Romans forbade the building of new synagogues, but by the third century AD they were allowing them again. Archaeologists have identified more than a hundred in the land, dating from the third to the eighth centuries.

{mospagebreak title=Logistics}

Logistics

Telephone 08-6584207/8

The staff attempts to do all the maintenance work on the cable car after closing hours, but it is prudent to check. Under severe weather conditions, the cable car may be closed, and/or the Snake Path may be closed.

Nature Reserves and National Parks (Main office: 02/500-5444)

Opening hours:

April 1 through September 30, from 0500 - 1700

0500 - 1700. (Entrance until 16.00)*

October 1 through March 31, from 0500 - 1600

0500 - 1600. (Entrance until 15.00)*

*On Fridays and the eves of Jewish holidays, the sites close one hour earlier. For example, on a Friday in March one must enter by 14.00 and leave by 15.00.

The cablecar operates on the half hour or whenever 40 passengers are gathered.

Starting an hour before sunrise, one may climb Masada on foot, using either the Snake Path from the east or the Roman ramp from the west. Wear good walking shoes, bring water, have both hands free, protect your head from the sun and do not attempt shortcuts. It is wise to avoid the Snake Path during the hot hours of summer days.

Call Send SMS Add to Skype You'll need Skype CreditFree via Skype